Triggering compassion

Peasant Mother and Child, 1894, Mary Cassatt

A dear friend of mine, Florence Wetzel, wrote about trigger warnings as she was getting ready to publish a novel. A trigger warning is a statement disclosing that a work contains content that could be upsetting, inviting the reader to pass it over. Wetzel considered one, as her book discusses abuse. She elected not to include it, though she does give the reader some idea of the work’s contents on the jacket cover.

What does it mean to be triggered? In psychology, this refers a stimulus that leads to a flashback, or intense reexperiencing of a previous trauma. For example, a veteran may have sudden, vivid memories of combat in response to hearing explosions during an action film, or to smelling gasoline. However, most people aren’t referring to flashbacks when they say “triggered”; colloquially, the word has expanded to include something that causes a person to feel uncomfortable or nervous.

Trigger warnings are a well-intended, as some people experience considerable distress when exposed to certain concepts. Giving a heads up seems courteous. However, there is another side to this. A recent metanalysis shows that people experience more distress after viewing the same content with a trigger warning then when it lacks one. They can encourage avoidance, which is counterproductive to treatments for anxiety and related disorders as avoiding perpetuates the anxious state. Johnthan Haidt discusses that trigger warnings can reinforce distress through the cognitive distortion of fortune telling: predicting that one will feel upset any time content is viewed. Treatment conversely involves gradual exposure to what’s causing anxiety, alongside coping skills and a supportive therapeutic relationship.

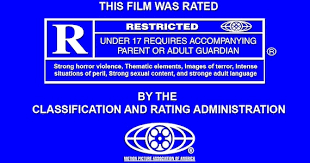

Still, it’s understandable that people may not want to engage with a topic. But suggesting that content will harm can cause people to feel more upset. Warnings that are neutral, such as those created by the Motion Picture Association (ratings G, PG, PG-13, R) provide an idea of what a work contains without suggesting that it’s damaging. Alongside each rating there is a justification (nudity, substance use, strong language, violence). These ratings are appreciated. No one wants to watch sex scenes during a multigenerational holiday gathering. They suggest that some films aren’t suitable for children, but don’t imply that they are psychologically harmful for adults. A similar system could be applied to literature. Some authors are already using the more neutral term “content warning” instead of “trigger warning.”

Is there a reason why we should view content that could upset us? Not just sound bytes, snippets of a plane crash or war, but the deeper account of human struggle that a novel provides. Books show an intimate view of someone outside our circles. From Wetzel’s article:

What is the role of literature? I mentioned earlier that “certain descriptions might cause undue pain.” But is this necessarily a bad thing, or something writers should avoid? Part of the magic of literature is its ability to expand our compassion, often as a direct result of feeling pain or discomfort while reading.

Our ancestors lived in small family groups, intimately connected with a few dozen others. Being in close proximity, we knew all about each other’s tragedies. In modern times, we all have a front door that we usually shut. We create bubbles of physical and psychological comfort: alone, or perhaps with our spouse and nuclear family. A few friends similar to us are included, as long as they are not too needy. I’ve often wondered if being less interested in others is a driver in our psychological distress.

We live in a world where we are increasingly suspicious of others. I believe that this is a factor in the loneliness epidemic, and in turn, in worsening mental health. People often ask me if I feel upset when I talk to patients about traumatic experiences. I tell them that it’s actually not hard, it’s wonderful, and an honor to do so. It helps me feel more open to the joy and tragedy that is the most intimate part of being human. Wetzel suggests that reading about another’s challenges can help us all in a similar way, that it could provide discomfort leading not to distress, but to growth, and to much-needed connection.